Julian Stanczak at Diane Rosenstein Gallery

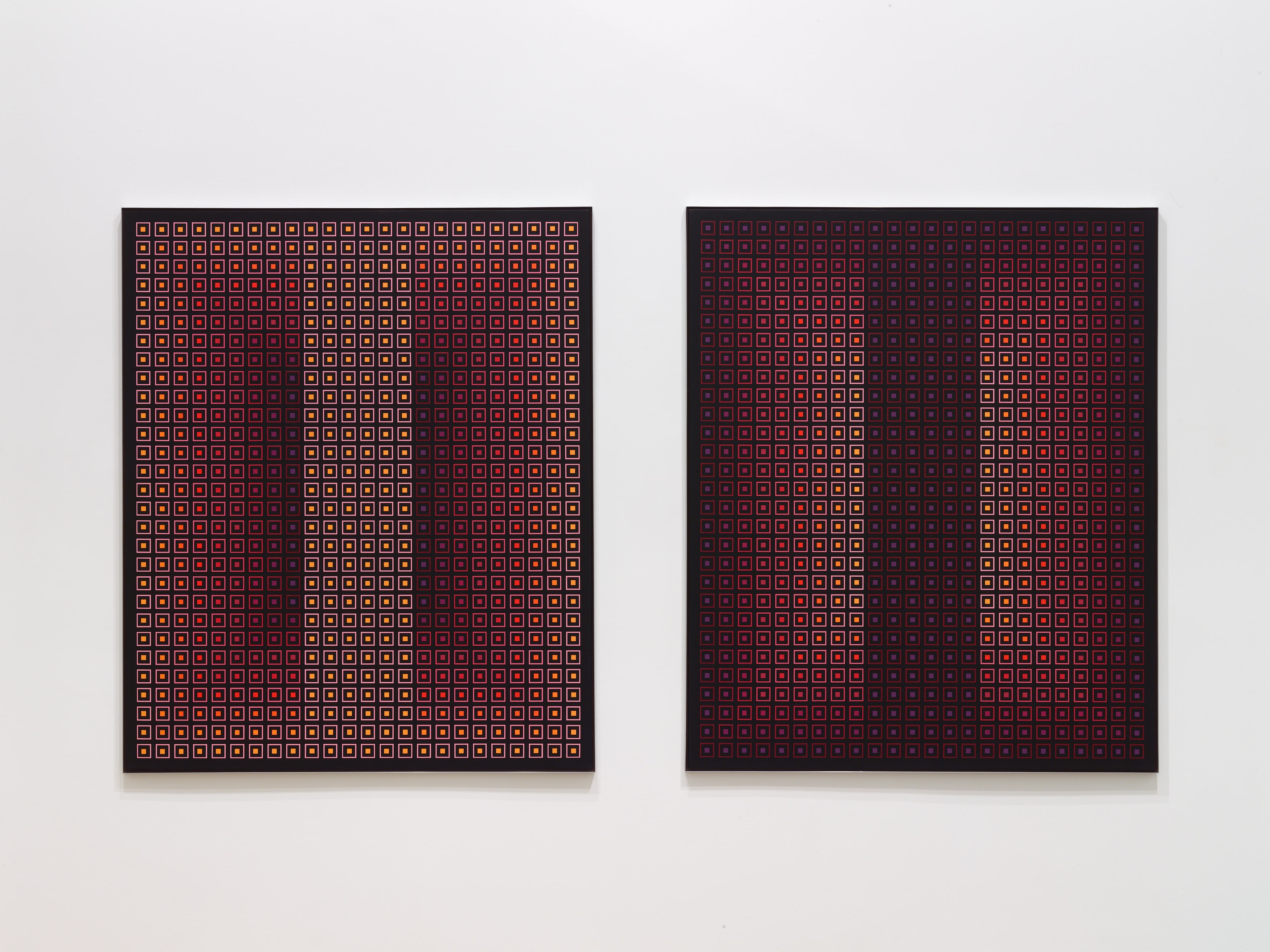

My last stop was “Julian Stanczak: The Eighties,” at Diane Rosenstein Gallery. Stanczak, who died in 2017, was an early practitioner of Op Art, a movement that originated in the 1960s, emphasizing the optical effects of an artwork and the mechanics of perception. The 15 works on view all date from the 1980s and reflect Stanczak’s utter dedication to the style. They consist of nothing but stripes and discreet, mostly rectilinear blocks of color, but are so masterfully planned and constructed that they generate luminous fields of light and color that seem to glow and hover off the gallery walls.

Beyond wondering at their technical prowess, it’s fun to glimpse into the proto-digital world of the 1980s. Now that gradients can be created simply by dragging a cursor across a screen, it’s a marvel to see how Stanczak created his analog versions. Rather than attempting to blend various hues together, he carefully orchestrated adjacent but discreet blocks of color to create subtle transitions. His paintings happen, not on the canvas but inside our heads, as our brains turn myriad tiny areas of flat color into luminous clouds of light. In some ways, Stanczak’s painting process was proto-algorithmic, creating an overall effect through the consistent, application of an evolving set of rules. They are masterworks of control that end up being strangely numinous.

Walking back to my car, I passed a Sherwin Williams paint store, a decidedly less mystical version of the kaleidoscope I’d just seen in the gallery. Simply giving up some of my power to choose — selecting a neighborhood rather than an exhibition, and walking instead of driving —allowed me to see immediate connections between art and the everyday that were previously more intellectual than felt.

I saw more powerfully how art refines and focuses chaos, pointing at things we might not otherwise notice, or heightening and affirming feelings we are afraid to acknowledge. It can do this because it occupies a distinct space: the rarefied world of the gallery or museum. But like Stanczak’s separate colors, art and life sometimes mix to make something more mysterious and beautiful than either of them can muster by themselves.